The Making of "The Industrial City"

According to archeologists, San Bruno Mountain was first settled about 5,000 years ago and may have been the first location on the San Francisco Peninsula to be inhabited.

The native peoples who occupied the San Francisco Peninsula at the time

of European contact are known as Costanoan, a term derived from the

Spanish word "Costanos" meaning coast people. Native Americans currently living in the Bay Area prefer the term "Ohlone" meaning "abalone people". These people settled on and around San Bruno Mountain, subsisting on hunting, fishing, and gathering mussels, shellfish, and native plants. Middens or shell mounds that date back thousands of years, are found in Buckeye Canyon, the eastern slope of the Southeast Ridge, and the inland sand dunes

in Daly City.

With the Spanish entry into the San Francisco Bay Area in 1769, the

traditional Costanoan/Ohlone way of life rapidly deteriorated as native populations and cultures were decimated by introduced diseases, a declining birthrate, the impacts of the mission system and, beginning in 1833, the secularization of mission lands by the Mexican government. The Ohlone

were transformed from hunters and gatherers into agricultural laborers who lived at the missions and worked with former neighboring groups such as the Yokuts, Miwok and Patwin.

The City of South San Francisco had its beginning in the fertile brain of

Peter E. Iler of Omaha, Nebraska.

In 1835, Mexico granted José Antonio Sánchez, a noted soldier, 15,000 acres

of land from Millbrae to Colma. He maintained his casa grande in Millbrae, until his death in 1843. The land was then divided equally among his ten

sons and daughters.

Just south of the present day cemeteries in Colma was an early farming community called Baden. This hamlet occupied a small part of the old Buri Buri Rancho that had belonged to José Antonio Sánchez. In 1856 cattleman, Charles Lux, owner of a larger butchering business in San Francisco, acquired 1,500 acres for $18,000 from Alfred Edmondson. Three years earlier Edmondson had bought from José’s son, Isidro, his entire one-tenth inheritance of Rancho Buri Buri for only $10,000.

Here Lux built an elegant home near tidewater on Colma Creek at what came to be known as Baden, where a small wharf could be built. Just north on Mission Road stood Baden’s 12 Mile House, dating back to at least 1853. Small dairies, vegetables farms and fields of flowers eventually occupied the surrounding countryside.

It was at Lux’s Baden home, located in the block bounded by Oak Street, Mission Road, and Commercial and Chestnut Avenues, that Lux formed his famous partnership with Central Valley rancher Henry Miller, launching California’s largest 19th century livestock company. For more than thirty years, drovers herded thousands of cattle from the firm’s big Central Valley ranches into the Bay Area and up El Camino to Lux’s Baden spread. There they the cattle were held and fed on grass before being driven the last few miles into the San Francisco stockyards.

At the time of his death in 1887, Charles Lux owned well over 3,000 acres of prime undeveloped land. When Gustavus F. Swift came west in search of a site for a Pacific Coast meat packing center, he found exactly what he was looking for on the Lux farm. Swift saw at once that not only was the site near San Francisco, with transportation available by both water and rail, but it was also situated where prevailing winds would carry the offensive fumes of the slaughter houses out over the Bay.

His plan was for all of the large meat packing firms to join in establishing a stockyard to serve the packing plants that they would build.

Omaha businessman, Peter Iler was hired to select a site for their California meatpacking operations. Iler chose Point San Bruno at the water’s edge, and up-wind toward the west would be the town where the employees would live. With the backing of a syndicate of Chicago meat packers, headed by Armour, Swift, Michael Cudahy, and Nelson Morris, Iler optioned on 3,500 acres fronting on the bay of South San Francisco at San Bruno Point including the the Lux Ranch in 1890. Thereupon South San Francisco Land and Improvement Company was incorporated, with Peter Iler as general manager to promote and develop the town.

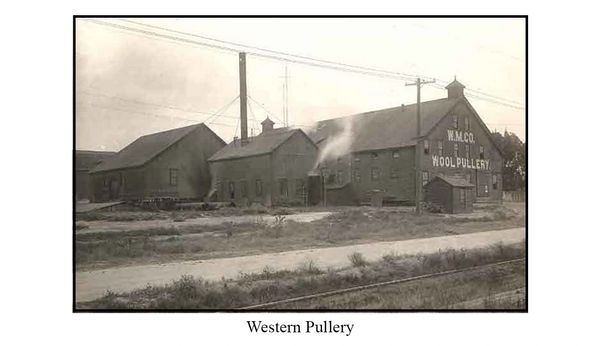

Other prominent backers included San Francisco bankers Henry Crocker and Philip Lilienthal, and Lux’s surviving partner, Henry Miller. However, there was fierce opposition to this bold venture; the established butchers of San Francisco fought it with the heaviest pressures they could bring to bear–with the result that all but Swift himself withdrew from the project. He refused to be intimidated and carried on alone. In 1892 he established the stockyard and Western Meat Company. Acres of land fronting on the harbor were conveyed by the Land Company to the meat company as a site for stock yards, abattoirs and a meat packing plants – as well as sites for by - product factories such as glue, works, wool pullery, etc. (In later years, Armour & Co. came into the enterprise and, to this extent, at least, Swift’s original dream was fulfilled).

William J. Martin and Ebenezer Cunningham, Omaha friends of Iler, soon arrived in the new community and both would play important parts in the early development of South San Francisco.

In April 1892, W. J. Martin was appointed land agent for the South San Francisco Land and Improvement Company. Under his direction,

the town began to take shape and he began a ceaseless campaign for the industrial development of this city. Through his efforts, factory after factory located here until a score of great manufacturing industries were gathered prompting South City’s moniker, “The Industrial City.”

Follows is just a sampling of the other industries that eagerly moved into South San Francisco:

• Steiger Terra Cotta and Pottery Company (1894)

• Baden Brick Company (1894)

• W. P. Fuller Paint Oil and Lead Company (1898)

• South San Francisco Lumber and Supply Company (1898)

• Pacific Coast Steel Company (1909)

• Schaw-Batcher Pipe Company (1913)

The residential section began on a small plat west of the present Bayshore Freeway. At Grand and Cypress Avenues the first house in South San Francisco was built in November 1891. That same month William Martin erected the second building in town – which he used as a real estate office. In the early years, population in the residential area grew almost as impressively as industry. By 1895 the town had 671 residents (354 men, 146 women, 171 children). To encourage settlement, in 1894 the Land Company helped build the north county’s largest school – a spacious, two-story structure which took in pupils from kindergarten through high school.

After working as a land agent, Ebenezer Cunningham was appointed postmaster and elected justice of the peace. In 1895 he began publishing

The Enterprise – a weekly newspaper that preached harmony between employers and works and promoted the town’s attractions to the rest of the Peninsula. Two San Francisco businessmen published its predecessor,

The News, briefly during 1892.

On July 15, 1905, the Bank of South San Francisco was incorporated and opened for business with a paid capital of $50,000.

By 1906 the town had a population of nearly 1,500 and had eclipsed

the old hamlet, Baden, though some stubbornly continued to refer to

the entire area as “Baden.”

Under the able promotion of William J. Martin, South City grew large enough by 1908 to become a city of the sixth class with nearly two thousand inhabitants. On September 3, 1908, South San Francisco was incorporated and the following citizens were chosen as city officials:

Trustees:

Harry Edwards

Andrew Hynding

Thomas L. Hickey

Daniel McSweeney

Herman Gaerdes

Clerk: Thomas Mason

Treasurer: C.L. Kauffmann

Marshall: Henry Kneese

In its early days, South San Francisco boasted a fine hotel, a Carnegie Library, a progressive newspaper, a primary, grammar and high school, and a well-equipped hospital. There were also three churches:

Grace Episcopal, Methodist Episcopal, and Catholic.

South City greeted the 1920s with enthusiasm, prosperity and continued growth. By then the town had expanded to 2,420 residents and new houses filled the area of north Linden Avenue. Martin School and Siebecker Park

were built to accommodate families now living in that area.

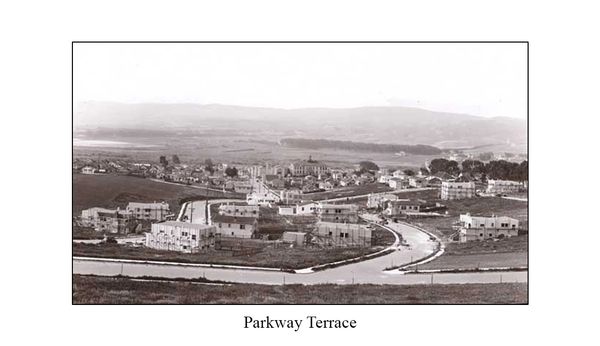

Parkway Terrace was developing along Palm, Magnolia, Commercial and

upper Orange Avenues. Orange Avenue Park was built on former marshland that used to be known as “The Willows.” By 1928 the new Magnolia Grammar School was standing next to earlier elementary school buildings on the corner of Magnolia and Grand Avenues.

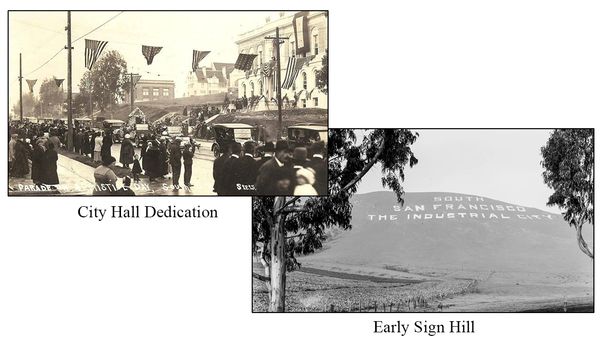

The new city hall was dedicated in November 1920 and in 1924 tennis courts were built where the city hall parking lot now stands. Our “Industrial City” sign was originally whitewashed on Sign Hill in 1923. A bond issue to make the letters permanent was passed with the help of the Chamber of Commerce in 1928 and the present sixty‐foot concrete letters were constructed in 1929. “The sign will be the best advertising asset that this city ever had,” declared Chamber President E. P. Kauffman.

Pedestrians, autos, and streetcars maneuvered along the bustling

Grand Avenue. The Palace Meat Market opened in the new

Vincenzini building. Movies flickered at a nickelodeon on

Grand Avenue and later at the Royal Theater on Linden.

The popularity of new auto and airplane industries brought more businesses:

• Fred Lautze Ford (1920)

• Friesly Aircraft Co. (1920‐ 24)

• Union Oil Co. (1920)

• Richfield Oil (1925)

• Colma Motor Car Co. - Buicks (1927)

• Cook Oil Burner Co. (1928)

• E. Bendinelli & Co. ‐ Lincolns (1927)

• Marchette Motors (1928)

• Enterprise Oil Burner Co. (1929)

• Standard Oil (1929)

However, major industries in town continued to be meat packing and steel industries and steel ‐ related industries that came during this decade included:

• Metal & Thermit (1920)

• Wildbery Bros. Refinery (1920)

• Specialty Wire Co. (1927)

• Michel & Pfeffer Iron Works (1929)

• Western Metal Co. (1929)

Other new businesses welcomed to industrial park:

• Fontana foods‐ Macaroni (1922)

• McClellen Orchids (1926)

• Barrett Co. (1927)

• Morrill Ink (1927)

• Gueren Bros. (1927)

• Pacific Gas and Electric Co. (1929)

When the depression hit in 1929, the economy severely slowed and factory orders all but came to a halt. Factories were forced to lay off many workers, while others were asked to share shifts so that what pay there was could be spread among their families to live upon.

Many children had to quit school and take work to provide income

for their families. Sixty-five students from the South San Francisco

Junior-Senior High School teamed up with the PTA and formed a soup

kitchen at the grammar school.

The building of the Golden Gate Bridge in the early1930s brought a windfall

to South San Francisco’s Edwards Wire Rope Company, which supplied

all the wire cable for the bridge.

The Baden Kennel Club (a greyhound racing track) opened in 1933.

It employed many who had lost work in the factories. But those jobs came

with controversy and concern. Wagering was illegal and the track was raided several times and many residents were concerned about the criminal element

it track attracted. When the state outlawed greyhound racing, the Club was forced to close in 1938.

Works Progress Administration (WPA) was established in 1935 and the

agency had a dramatically beneficial effect on South San Francisco. WPA programs made improvements to Orange Park, moved land from nearby

hills for San Francisco Airport bay fill, and built the new Post Office on

Linden Avenue. Through the program, painter and muralist Victor Arnautoff was chosen to paint murals at Linden Avenue Post Office. Arnautoff,

a prolific artist and former assistant to Diego Rivera, also painted murals in Coit Tower through the Federal Art Project. Luckily, those murals still

grace the walls of the Linden Avenue Post Office.

South San Francisco had a reputation as a wild and woolly blue-collar town. Gambling, liquor and prostitution all added to our colorful past. Yet, many

local residents look back at those years and recall how willing everybody

was to help each other. By 1930, South San Francisco had a population of

5,000 people, and was a small, close-knit community – it was like a family.

Major industries continued to locate in South San Francisco and two world wars brought a transition to shipbuilding: Shaw-Batcher and Belair. The Shaw‐Batcher shipyard built cargo ships and between wars it built barges and dredges and fabricated pipe, - becoming one of the pioneers of automatic welding machinery. The shipyard in South San Francisco had four berths from which ships were uniquely launched sideways – two on each side of a large basin at Oyster Point. Following World War II the population boomed and a well‐balanced community of industrial and residential areas developed.

The 1950s brought modern industrial parks to the East of Freeway 101

area, such as Cabot, Cabot and Forbes. Freight forwarding, light industries,

and other airport-related businesses thrived.

A new era for South San Francisco began in 1976 with the founding of Genentech by venture capitalist Robert Swanson and molecular biologist

Dr. Herbert Boyer. Their objective was to explore ways of using recombinant DNA technology to create breakthrough medicines. This earned South San Francisco the new moniker "Birthplace of Biotechnology" and thus attracted other biotech and pharmaceutical businesses to the area.

History has proven that South San Francisco is resilient and resourceful;

it evolves and transforms with the times – always up for challenges and

a new beginning.

Historical Resource Links

In partnership with the South San Francisco Public Library and the City of South San Francisco

Historical Society of South San Francisco

80 Chestnut Avenue, South San Francisco, California 94080, United States

Get Social & Get Involved

Winter Break!

The Plymire-Schwarz House is taking a winter break.

Regular hours will resume

Saturday, February 7, 2026 (1:00-4:00)

The Museum remains open with regular hours:

Saturdays

1:00 - 4:00